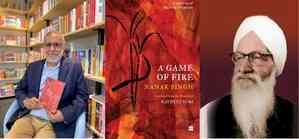

A twilight, amoral world: Some Cold War spy fiction (Column: Bookends)

Think espionage and the first image flashing in your mind will be of a suave, smartly-clad "secret agent" pulling off the most complex mission single-handed. A raised eyebrow and a wisecrack is his only reaction in a tight position he finds...

Think espionage and the first image flashing in your mind will be of a suave, smartly-clad "secret agent" pulling off the most complex mission single-handed. A raised eyebrow and a wisecrack is his only reaction in a tight position he finds himself in before busting out spectacularly with aid of a range of awesome gadgets. But is the cinematic depiction of James Bond the way spies and secret agents operate? Not much.

The best spies work without drawing attention and experts contend that flamboyant operators like the film James Bond, operating under their real names and flimsy cover, will not last much beyond their first missions with their forewarned adversaries waiting for them the next time.

The bulk of the James Bond films are examples of what the hugely informative and entertaining tvtropes.org terms the "martini-flavoured" or "tuxedo approach" to spy fiction where adjectives like glamourous, fast, hot and cool can be paired with nouns like parties, cars, womenand gadgets as per your wish. All the examples - films and books - are often glamourized and idealistic with clearly-defined "good" and "bad" people though this profession is never so clear-cut.

It is the other, more gritty and considerably darker variety - the "stale beer" or the "trenchcoat" approach that is a closer reflection of the twilight world of betrayal, bluff, deception, moral ambiguity and more painstaking mundane activities - that espionage is in reality. Older than the martini version, it is now seeing a resurgence in a world beset with new forms of conflict even though the era it described - The Cold War - is long gone.

The James Bond novels by Ian Fleming are the best examples as are the works of authors like John Le Carre, Ted Allbeury, Len Deighton, Robert Litell, Robert Ludlum (the Jason Bourne series) and so on. Spying here is a facet of power politics between the countries or organisations involved and often other nations and people get caught in between.

Protagonists will generally be far from physically prepossessing, quite often be flawed with deteriorating private lives, and more likely to be more concerned - often to the verge of paranoia - about their colleagues rather then their adversaries.

"What the hell do you think spies are? Moral philosophers measuring everything they do against the word of God or Karl Marx? They're not! They're just a bunch of seedy, squalid, bastards like me: little men, drunkards, queers, hen-pecked husbands, civil servants playing cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten little lives. Do you think they sit like monks in a cell, balancing right against wrong?" says the "hero" of Le Carre's "The Spy Who Came in from the Cold" and he is not off the mark.

The 1963 novel by the former intelligence operative is a benchmark of this variety of spy fiction, with its underlying, scarcely comfortable message - that the employers are concerned with the results of their stratagems, not the cost to their agents.

Then there is Le Carre's equally classic Karla trilogy - "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy" (1974), "The Honourable Schoolboy" (1978) and "Smiley's People (1979)" - which again brings out the blurred lines between rival entities. The quest to achieve the result - the defection of a top Soviet spymaster - sees our "hero" George Smiley employing blackmail to serve his ends against his nemesis, whose love for his daughter trumps any other considerations.

Authors like Litell weave in real life incidents and characters to lend verisimilitude to their works. "The Company" is a captivating, multi-generational saga of four decades and more of CIA operations as the narrative races across a canvas spanning from Berlin of the 1950s, the Soviet invasion of Hungary, the Bay of Pigs, the Afghan war and the 1991 coup against Gorbachev, among others.

At heart a relentless mole hunt, it brings in the Kennedy brothers, Fidel Castro, Yuri Andropov, CIA chiefs like Allen Dulles and Richard Helms, paranoid CIA counter-intelligence czar James Jesus Angleton, Ronald Reagan and a fine cameo appearance by the man we now know as Vladimir Putin to create a definitive story of clandestine activities of the late 20th century.

Then there is Edward Wilson's elegantly-crafted, morbidly fascinating "The Envoy" (2009), set in Britain of the 1950s and underscoring how your adversaries are not the only people you spy on and try to subvert.

The tale is carried on, with a change of focus, through a trilogy, starring William

Catesby, whose working class-origin is not quite in line with the privileged echelons of the higher reaches of British intelligence.

"The Darkling Spy" (2010) has a setting and tone reminiscent of the "The Spy Who Came in from the Cold" (and nearly equally harrowing ending). Next comes "The Midnight Swimmer" (2012), set around the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then "The Whitehall Mandarin" (2014).

The Cold War has ended in the real world but lives on in the realm of spy fiction!

(06.07.2014 - Vikas Datta is a senior assistant editor at IANS. The views expressed are personal. He can be contacted at [email protected])

cityairnews

cityairnews