Narendra Modi: The grassroots leader who challenged India’s political elite

Narendra Modi’s rise in Indian politics cannot be understood through the traditional lens of privilege. Unlike many leaders nurtured in political dynasties, Modi and his leadership style emerged from the soil, shaped by his struggle, years of grassroots work, and field experience across different levels of government. His career represents not just the ascent of one man, but a challenge to the very foundation of elite‑driven politics in India.

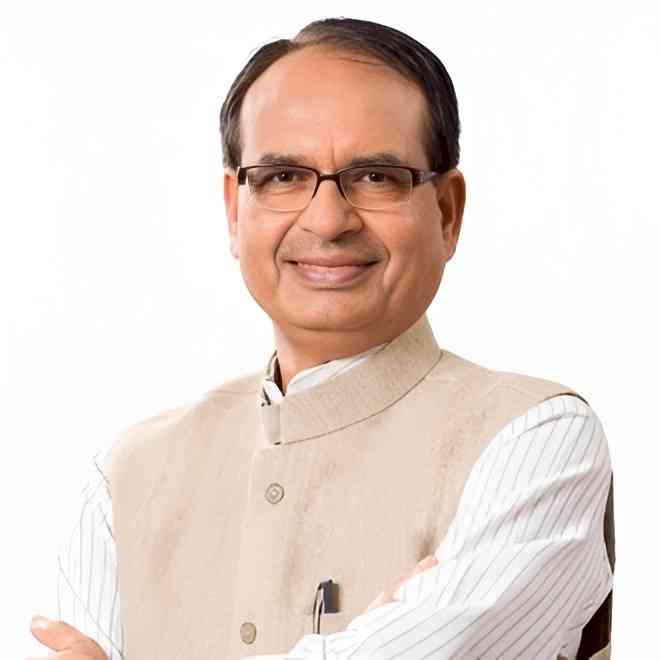

By Shivraj Singh Chauhan, Union Minister for Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare and Rural Development

Narendra Modi’s rise in Indian politics cannot be understood through the traditional lens of privilege. Unlike many leaders nurtured in political dynasties, Modi and his leadership style emerged from the soil, shaped by his struggle, years of grassroots work, and field experience across different levels of government. His career represents not just the ascent of one man, but a challenge to the very foundation of elite‑driven politics in India.

Born in a modest household in Vadnagar, Modi’s childhood was marked by responsibility and simplicity. From setting up charity stalls in aid of flood victims to writing a play on caste discrimination as a schoolboy, he displayed an exceptional mix of organisational acumen and social concern at a young age. He also ran campaigns to collect used books and uniforms for underprivileged classmates, an early sign that he was already thinking about leadership in terms of service, and not as a privilege. These small efforts foreshadowed the approach he would carry into public life.

His grassroots instincts were sharpened in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), where ordinary workers were instructed to interact with villagers, live as they lived, and earn trust through their conduct. As a young pracharak, Modi did exactly that. Often travelling across Gujarat by bus or scooter, and depending on villagers for food and shelter, he built trust across the board through shared hardship and struggle. This discipline kept him rooted in the everyday concerns of the people he was looking to serve, and it prepared him to lead effectively when crises demanded organised, large‑scale responses.

One such crisis was when the Machhu Dam collapsed in 1979, killing thousands. A 29‑year‑old Modi immediately mobilised volunteers in shifts, organized relief materials, retrieved bodies, and consoled families. A few years later, during a drought in Gujarat, he spearheaded the Sukhdi Abhiyan, which expanded across the state, distributing food worth nearly 25 crore rupees. In both disasters, he built large-scale relief efforts from scratch, demonstrating his clarity of purpose, his military-style organisation, and his insistence that leadership meant service, not just symbolism.

While these earlier episodes tested his ability to mobilise people, the Emergency tested his courage under repression. At just 25, disguised as a Sikh, he maintained communication between activists and leaders seeking to evade police surveillance. This grassroots network kept resistance to the draconian regime alive, earning him a reputation as a master organiser.

The same skills were soon channelled into electoral politics. As the BJP Gujarat’s sangathan mantri (organizing secretary), he expanded the party across new communities, including those marginalised in political discourse. He nurtured leaders from diverse backgrounds, consolidated ground-level support, and helped in planning major events like the LK Advani’s Somnath-Ayodhya Rath Yatra across Gujarat. Later, as prabhari (in-charge) in different states, he built strong party machines rooted at the booth level.

When he became Gujarat’s Chief Minister in 2001, Modi applied these lessons to governance. Mere hours after taking office, for instance, he had convened a meeting on bringing Narmada water to Sabarmati, indicating how decisive action would come to define his administration. His approach was to make governance into a people’s movement, where the Praveshotsav encouraged school enrolment, Kanya Kelavani supported girls’ education, Garib Kalyan Melas took welfare to citizens, and Krishi Rath brought agricultural support to farmers’ fields. Bureaucrats were pushed out of offices into towns and villages. He remains of the view that governance much reach people where they live, not stay confined to conference rooms.

These experiments in Gujarat became national templates once he became Prime Minister. His experience with cleanliness campaigns evolved into the Swachh Bharat Mission, where he picked up the broom himself to turn symbolism into mass action. Digital India, Jan Dhan Yojana, and other initiatives were not top‑down programmes but people’s movements rooted in the learnings from his years spent at the grassroots. They embodied his philosophy of jan bhagidari, where governance works only when citizens become participants rather than passive recipients. This trust between a leader like Modi and the people, cultivated over decades, is what has turned policy into partnership in today’s India.

Over decades, Modi has shown a rare instinct for knowing what people need and how to deliver it, not from drawing‑room debates, but from lived connection with the ground. That instinct, combined with hard administrative experience, has come to define his politics.

Ultimately, his life and leadership rewrite the idea that Indian politics belongs only to elites. He has become a symbol of merit and hardwork, and brought governance closer to ordinary people. His political strength lies in connecting power to the people. In doing so, he has reshaped Indian politics, rooted in the struggles and the spirit of the common citizen.

(Views are personal)

City Air News

City Air News