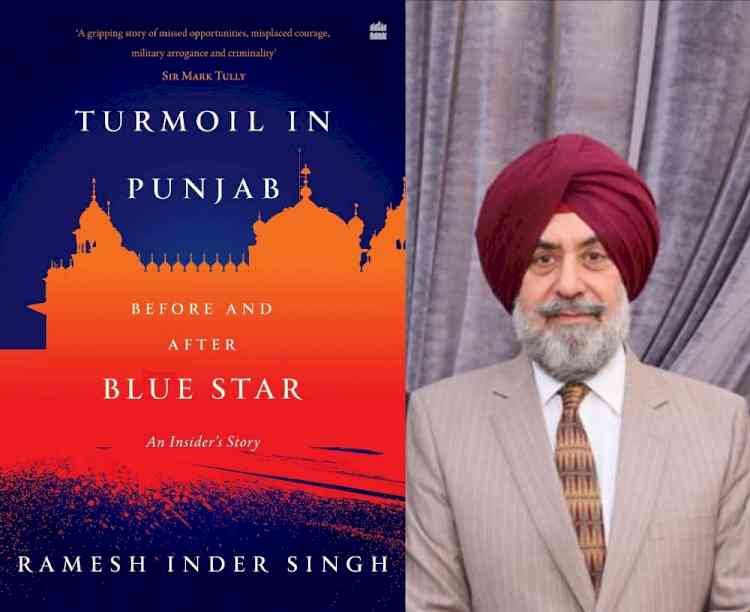

Intriguing questions rekindled 38 years after Operation Blue Star (Book Review)

Did the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi bypass the chain of command and force the Indian Army's hand into launching the "ill conceived, poorly planned, terribly executed" Operation Blue Star by compelling an ambitious army commander to pull "the carpet out from under the feet" of the army chief?

Vishnu Makhijani

New Delhi, July 13 (IANS) Did the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi bypass the chain of command and force the Indian Army's hand into launching the "ill conceived, poorly planned, terribly executed" Operation Blue Star by compelling an ambitious army commander to pull "the carpet out from under the feet" of the army chief?

Would the course of history have been different if the heavily-armed militants holed up inside the Golden Temple had been asked to surrender as this "could have delegitimised them in the public eye" had they failed to do so?

Why were the instructions issued in 1982 by an army commander on the "procedure for conducting such an operation" if necessary, that included its videotaping and inviting two prominent but non-political Sikhs to witness the operation, ignored?

These are some of the intriguing questions that have been rekindled by a new thoroughly-researched book, 'Turmoil In Punjab - Before And After Blue Star - An Insider's Story' (HarperCollins) by Ramesh Inder Singh, who was the District Magistrate of Amritsar from 1984 to 1987 and went on to become the state's Chief Secretary, who terms Operation Blue Star "a black chapter in our history" that "continues and probably will continue to cause pain for a long time to come".

"The plans for the attack were ad hoc, and virtually all basic tenets of fighting in a built-up area were ignored...The most obvious lesson was: never bypass the chain of command. The genesis of the entire problem lay in the Prime Minister inviting the Western Army Commander (Lt. Gen. K. Sundarji, who went on to become the army chief) to her residence when the decision to involve the army was taken. The events that were set in motion that day eventually cost the Prime Minister her own life," the book quotes General V.K. Singh, a former army chief and a minister in the current government, as noting.

"The moment General Sundarji pulled the carpet out from under the feet of the COAS (Chief of Army Staff General A.S. Vaidya), the military logic had compromised and each subsequent decision was guided by political rather than operational logic. It also underlined the fact that someone somewhere along the line had to have the gumption to point out that the situation was being handled wrongly. This never happened and Army HQ effectively became a spectator," Gen. V.K. Singh adds.

Ramesh Inder Singh, who was awarded a Padma Shri in 1986 at the age of 36 for his notable contributions in the field of public administration, writes that he has "often asked people about how they perceive Operation Blue Star - was it an assault on the Golden Temple or was it an operation to clear the temple of the armed radicals who had laid siege to the hallowed space and posed a challenge to the legitimacy of a constitutionally established polity"?

Not surprisingly, he writes, most Sikhs viewed Blue Star "as a premeditated, sacrilegious invasion of their holy shrine. And that explains the backlash that followed the operation; it synthesised the sentiments of the quam against the state as a collective voice. In the battle of public perception, the state had miserably failed to carry the community along. This was, more than any other factor, the cause of the fatal consequences that followed Blue Star, and it continues to haunt the community even today".

In matters of faith, they say, reason usually is the first casualty. Sacrosanct spaces require emphatic handling; the holier a hallowed place, the greater the sensitivity of the faithful, and still stronger their reaction if in their eyes its sanctity is violated. The state ignored this sentiment and the consequences were catastrophic.

"Still worse was the way Blue Star was carried out. It was a disaster - ill conceived, poorly planned, terribly executed. Consequently, for the troops it was a pyrrhic victory. A few hundred militants were killed. But their death sowed the seeds for ethno-religious nationalism to proliferate and generate a violence far worse than what the operation had eliminated. Blue Star was not the epilogue, but a prelude to the violent struggle for Khalistan. The army won the battle, but at the cost of peace in Punjab," Singh writes.

As the events unfolded, he writes, it became obvious that the Central leadership and the key military advisers were not conscious of the public sentiment or the political consequences of launching a direct assault on the sacred space. The troops deployed in the operation were oblivious to Sikh sentiments. Hurriedly inducted without familiarisation with the area or the layout of the temple precincts, a frontal assault on a well-fortified built-up area without cover or camouflage against religiously motivated militants was suicidal. There could only be one kind of outcome - death and destruction. The holy space was desecrated, soldiers were massacred, a large number of innocent civilians were killed and collateral damage was prohibitive.

Anticipating a situation where the army may be summoned to aid the civil administration, Lt. Gen S.K. Sinha, the then GOC-in-Chief, Western Command, had issued instructions in 1982 on the "procedure for conducting such an operation" that included its videotaping and inviting two prominent but non-political Sikhs to witness the operation.

He had emphasised the need to execute the operation in a manner that would cause minimum alienation, and later regretted that the psychological aspect was not factored in and the mistake "cost us dearly".

"Those in command of Blue Star - and two of them were Sikhs - did not pay heed to what had been proposed earlier by the other generals, erroneously presuming that the operation would be swift; or rather they suffered from the illusion that the mere sight and rumbling of the heavy armaments, tanks and APCs, the flying choppers, and the numerical superiority and might of the army garrison would scare the militants out of their pigeonholes and they would not put up a fight. It was a fatal miscalculation," Singh writes.

It was a flawed strategy to presume that the militants would give up on their own. Consequently, at no stage did the troops appeal to the militants to surrender. The army commanders made no attempt to hold a dialogue or negotiate with the militants to forestall the armed confrontation. The troops launched the attack suo moto.

"The extremists under Bhindranwale, Bhai Amrik Singh and ex-Maj. Gen. Shahbeg Singh fought because they were given no option," observed Lt. Gen. V.K. Nayar, who had succeeded Sundarji as GOC-in-Chief, Western Command, in 1987-89.

"When the militants repulsed the attack, the top army brass responded by deploying more troops and weapons of higher calibre. When repeated frontal assaults failed, the APCs and tanks were employed, with catastrophic consequences," Singh writes.

The operation also invited censure from three iconic warriors - Lt. Gen. Jagjit Singh Aurora, hero of the Pakistani surrender at Dhaka in 1971 that resulted in the creation of Bangladesh; Lt. Gen. Harbaksh Singh, who saved the overrunning of Punjab by Pakistan in 1965, and the only Marshal of the Indian Air Force, Singh - particularly the way it was executed.

"The list of critics is long. Suffice to say that the armed solution in the absence of a political narrative to address the ethno-religious Gordian knot was rife with problems. Before launching the assault, attempts to seek a surrender from the militants could have delegitimised them in the public eye, if they did not surrender, the blame would lie squarely on the militants and not on the security forces for the operation's consequences," Singh writes.

The media blackout further led to the otherwise avoidable rumours of alleged excesses; it resulted in a loss of credibility for the State, as the press and public only saw the death and destruction in the aftermath of the military action and not the bloody attack the militants had unleashed on the army.

"The inappropriate choice of a day sacred to the Sikhs to launch the operation, the excessive use of force that killed a large number of innocent pilgrims and extensive damage to the sacred shrine alienated the Sikh community; that helped the radicals multiply their ranks, aided by Pakistan, post-Blue Star," Singh writes.

Much has happened since then and the author expresses his guarded optimism for the future.

Today, terrorism "has been eliminated decisively" from Punjab but "the deep, fundamental ethno-socio-religious fault lines that led to the turmoil in the state still persist", Singh writes.

"History has an uncanny habit of repeating itself, and we have to be on guard, for only the civilisations that draw lessons from their history and move forward prosper," he adds.

Noting that this is the earliest opportunity he received to publish the book post his superannuation as Punjab's Chief Secretary and thereafter as Chief Information Commissioner, Singh writes that he does not regret the interregnum "because the passage of years has helped crystallise issues and cooled down tempers. In these thirty-eight years, a lot has been said and written about Operation Blue Star and the chaos in Punjab. An abundance of pop history books and documentaries and a few eyewitness accounts - mostly hearsay - have been published. Everything, however, has not been said and probably may not be said for a while, considering the sensitivity of the subject and the security imperatives".

"I hope, as passions mellow over time, people within and outside the establishment will be more receptive of this work. My words may displease some; however, the intention is not to hurt any feelings or apportion blame - though in historical accounts this may be unavoidable - but to initiate dialogue, open the way to introspection and, most importantly, move toward reconciliation and closure over a tragic past," Singh maintains.

(Vishnu Makhijani can be reached at [email protected])

IANS

IANS