The forest is calling, but Van Gujjars cannot return

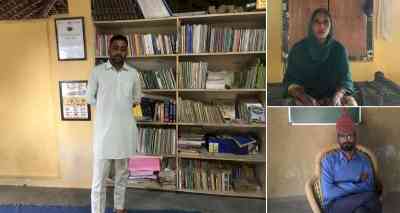

Dehradun, Dec 24 (IANS/ 101Reporters) "In olden times, the call of the Indian Cuckoo would tell us it is time to go to the mountains to graze animals," says Taukeer Alam, a Van Gujjar resettled at Laldhang from the Rajaji National Park area.

Van Gujjars belong to the Other Backward Classes in Uttarakhand, and are mainly found in Garhwal division. Their population stands at around 70,000 in the State. The contentious history of the relationship between this animal-rearing nomadic community and the van (forest) is more widely recorded than their ethos, which is intrinsically linked to forest conservation and sustainable use of resources.

For centuries, Van Gujjars have moved between hilly areas during summers, and plains during winters. They depend on natural resources for their survival. Hence, neither their customs nor daily lifestyle harm nature. "Even our deras (houses) are made of biodegradable materials from the forest. Once we leave an area, our houses decompose on their own," Alam tells 101Reporters.

"Before we were resettled here, we used to live in the forest. We could predict changes in weather just by noticing the behaviour of wild animals and the call of birds," Gullo Bibi tells 101Reporters. Bibi is a resident of Laldhang Gujar Basti, one of the colonies where the Uttarakhand government had resettled them from the park.

"Deer and nilgais used to come in search of warmth when we lit fires at night in the middle of our deras. They rest near our settlement and return to the forest only at dawn. That was the kind of relationship we had with the animals," she says.

"Now, you hear stories of wild animals moving towards the plains. Our colonies acted like a boundary between the forest and human settlement. The animals would only come up to our colonies and never move beyond. Now that we have been displaced, this border is getting breached," she says.

A fine example of coexistence

Though most of the forests in the hilly districts of Uttarakhand have been notified as wildlife sanctuaries, around 2,000 families living near Haridwar and Dehradun still migrate during summers to the barrage area built on the Ganga along the Muzaffarnagar-Bijnor district borders in Uttar Pradesh.

The practice of winter migration also continues, though it is not prevalent nowadays. "We still live in our old settlement in Gauri range of Rajaji Tiger Reserve near Rishikesh," says Mir Hamza, founder, Van Gujjar Tribal Youth Organisation. Notably, the Van Gujjar settlement in Gauri range is the only one remaining in Garhwal as its members have consistently dodged resettlement offers.

"To the east of our settlement is the east Ganga canal, and ahead of it is a dense forest. We come here after the winter migration, and the Gojri buffaloes we rear cross the canal to enter the forest, where they eat the half-eaten seeds and fruits thrown on the ground by monkeys and langurs. When they excrete on reaching back the settlement, the seeds fall here with the dung, helping in the growth of more trees," he explains.

According to Hamza, there were only shrubs and thorny trees like keekar and ber when they arrived at the resettlement area west of the canal in 2006. Today, different varieties of trees thrive there, mostly those their animals feed on.

Van Gujjars take buffaloes through different routes every day as the rubbing of cattle hooves tramples the grass and prevents its regrowth. This very line acts as a barrier against forest fires during summer.

"Our movement in the forest is also beneficial to herbivores. In summer, we chop tree leaves and drop them on the forest floor since there is a shortage of grass in the plains at that time. They are consumed both by our animals and those in the jungles," says Hamza, adding that they take care to cut only the branches without harming the trees.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a forest department official said, "During forest fires, we work jointly with Van Gujjars. Even when the department has to prune trees to aid in growth, we enlist their help. They are only stopped when they use more than the allowed forest produce." Without official forest rights, what is allowed or not is an arbitrary and unilateral decision by the forest department.

While acknowledging the role of Van Gujjars in conservation, Amit Rathi, a legal associate with the Centre for Pastoralism, states that wild animals can be easily spotted around their settlements, which negates the argument that conservation is only possible by removing the community from the forest.

Neither here nor there

Talks of resettling Van Gujjars first began in the 1980s, when the area was declared a tiger reserve. In the first phase of rehabilitation in 1994, 512 families were settled in Pathri village near Haridwar. Each family was given a house and 10 bighas of land inside the forest.

In 2003, another 881 families were settled in Laldhang near Gaindi Khata. Each family got 10 bighas of land outside the forest for cultivation and one bigha to build a house.

Speaking about her life after resettlement, Gullo Bibi says, "It has been 18 years. But even today, we do not have ownership rights to the land we cultivate. It belongs to the forest department. We are deprived of the government benefits that other farmers receive." She refers to the Kisan Credit Card, crop insurance and other cooperative schemes that farmers commonly access.

At the time of Van Gujjar rehabilitation, an agreement was made, according to which the land would remain with the forest department for the next 30 years and all the displaced families would continue to use it for agriculture. A decision on giving them land would be taken only after the 30-year agreement lapsed.

The way of life of Van Gujjars has completely changed after the rehabilitation. For example, about 1,400 families settled in Pathri and Gaindi Khata no longer migrate. They are full-time agriculturalists now. Those who received forest lands were inexperienced in preparing them for cultivation initially. Hence, they were leased out to local farmers for three years. A few Van Gujjars still follow this practice.

On why they have not made claims under the Forest Rights Act, 2006, Hamza says, "Most of the community members are not aware of it. We never had a formal education. Van Gujjar Tribal Youth Organisation was formed in 2017 to create awareness on such matters. Presently, we have 180 active members working mainly towards educating the community members about forest rights, biodiversity conservation and preservation of traditional knowledge."

The organisation also processes several applications and puts together documents to prove the historic link between the Van Gujjars and forests. However, only a handful of rights have been attained so far. One such is the granting of forest rights to around 60 families of a small settlement in Uttarkashi.

Senior officials of the Uttarakhand forest department did not respond to email queries on the impact that Van Gujjar resettlement has had on the forest.

This article is a part of 101Reporters' series The Promise Of Commons. In this series, we explore how judicious management of shared public resources can help the ecosystem as well as the communities inhabiting it.

(Satyam Kumar is an Uttar Pradesh-based freelance journalist and a member of 101Reporters, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.)

IANS

IANS